Self Portrait: Pan Yuliang’s Silken National Verity

The 20th century had exploded, following the overthrowing of the Qing Dynasty, the Republic Period thrust China into further political disarray (Zhu). As a response, merchants, former literati, and new painters mastered reinterpretation. Xieshi (realistic) and Xieyi (expressive) painting polarized the artistic realm, drawing inspiration from the Song and Yuan dynasties, respectively (Wang). And as much changed, one of the most interesting aspects of this period was the refocusing on education to include female artists, with many being sent to Paris and Rome to further their artistic studies, including none other than Pan Yuliang (Teo).

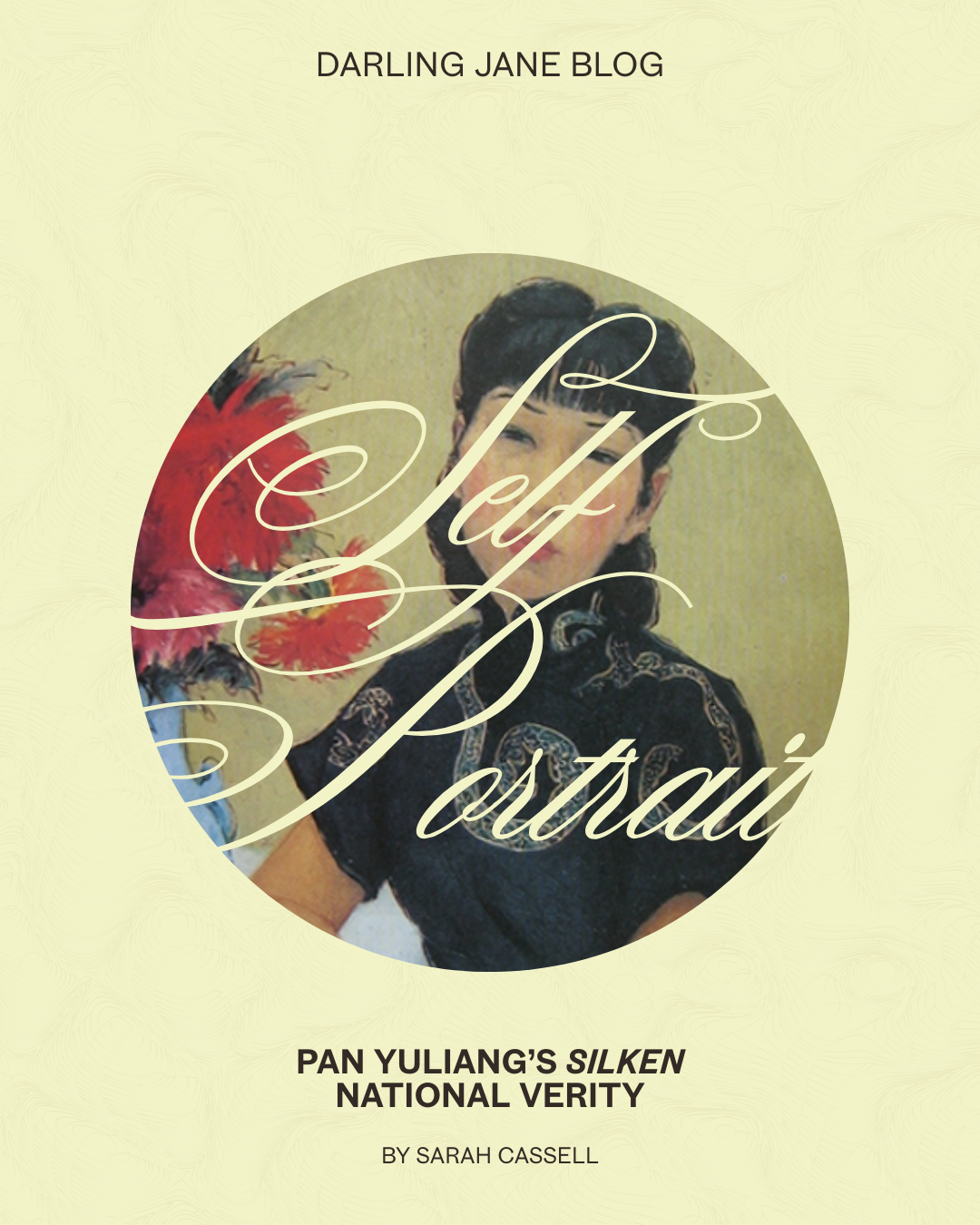

Pan’s mastery of the portrait is not just made up of her accuracy with anatomy, gorgeous use of hue, nor revolutionary representation of the female figure. But instead, her mastery of the portrait exemplifies her impressive ability to seamlessly blend traditional Han Chinese artistic training with Western Impressionist movements. This master of the craft allows Pan to create self-portraits that do not just represent the female body, but also represent the female soul. In doing so, Pan’s Self-Portrait shows how she truthfully sees herself, using Western techniques to recall traditional Chinese training and establish her Chinese identity, despite living and working in France.

While Pan Yuliang was incredibly talented, her work was often criticized and viewed as racy. Despite being a talented artist who later studied in Paris and Rome, Pan faced a ton of backlash during her rise to fame (Teo). Her background as an orphan from a lower class, ex-prostitute, and concubine muddied her reputation in the eyes of the conservative public (Teo). Even with the encouragement during the Republic for social reform and modernization, the traditional majority and high levels of conservatism restricted this work (Zhu).

On the other hand, this period brought the ability for female artists to level out the playing field of recognition and fame. Male artists, while training now in the same schools as female artists, had specific Chinese-based training that they were accredited to have excelled in. Yet, as the men were not exposed to Western styles, favoring traditional Chinese styles, achievements in Western painting garnered respect for female artists (Teo). Self-Portrait exemplifies how Chinese female artists gained power against the patriarchy by excelling in Western styles and responds to that call for modernization in The Republic Period. While many of her revolutionary phenomenal portraits show the female figure in a Western style– depicting women from different races, showing off body hair, displaying women breastfeeding in public (Teo)– Self-Portrait directly references her Chinese identity.

In Self-Portrait, Pan is resting in a chair, her arm draped over a table affixed with a white tablecloth and a vase of red flowers. Her face is set in a neutral position with her thin eyebrows raised, mouth in a natural line, eyeliner smoked upwards in a cat-eye style, and with rosy cheeks. She wears black modest Chinese clothing, determined as the qipao (Teo) by swirling silver patterns on the bodice, a fitted collar that covers the neck, and looser short sleeves. The primary colors to notice here are the yellow of the background, blue of the vase, black of the dress, nude of the skin, white of the tablecloth, and reds/pinks of the flowers. The flowers vary in color and hue for each petal, with varying brush stroke lengths forming unique blooms. Variation in color apparent in this painting draws similarities to European oil pastel styles– refer to Renoir’s Still Life with Flowers and Prickly Pears. There is additionally a stark difference in vibrancy between Pan and the blood-red flowers on the table.

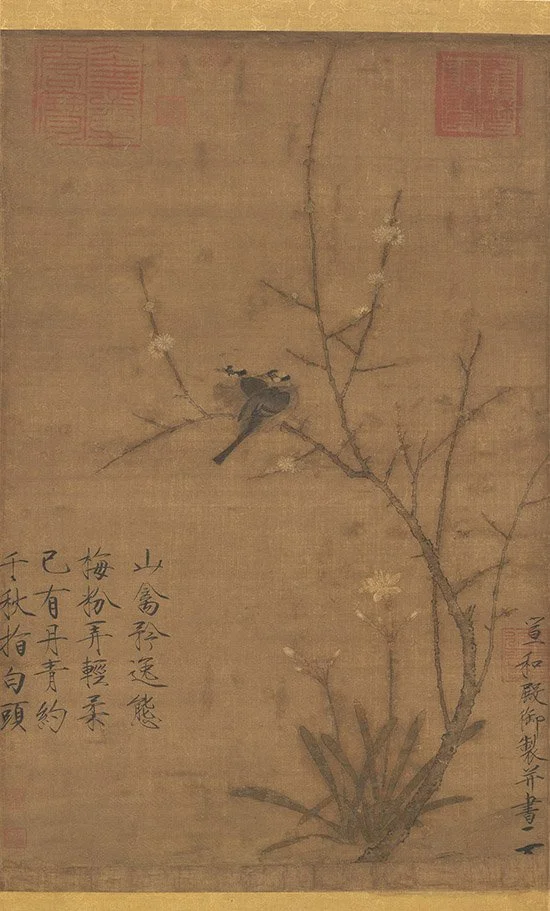

The Western training is apparent in Self-Portrait in many ways, even to a similarity in medium. The Chinese canon favors ink on silk, while Pan’s work is done with oil on canvas. The eye is drawn first to the blossoms, then to the table where the blue vase rests, then to the yellow background to spotlight the subject clad in black. This variation in color draws upon Western color theories of the color wheel, as opposed to the Chinese preference for muted colors and a limited palette. Furthermore, the composition of the petals themselves draw similarities to impressionist works like those done by the French Master Renoir, instead of the flowers that we see depicted in the Song and Yuan Dynasties, where other Republic works drew inspiration from.

While the painting uses Western style and technique, the work is seeped in Chinese heritage. Not only is the clothing itself a symbol of her Chinese identity, but the very decision to be fully clothed in this portrait considers her critiques of raciness from the Chinese public. As a result of this backlash, Pan could not succeed as an artist in China and was forced to move to Paris in 1937 (Teo). The muted colors of her body contrast with the bright flowers beside her, recalling the muted tones of traditional Chinese palettes alongside the ever-changing Western palette. Perhaps in leaving, Self-Portrait is a nostalgic musing on her nationality and heritage as a Chinese painter. Despite her move to Europe, she refuses to conform to European ideals and clothing. In using the visual tool of fashion, technique, and style, Pan Yuliang maintains her Chinese upbringing and honors her identity while embracing the modern Western changes in the artistic world.

Teo, Phyllis. Rewriting Modernism: Three Women Artists in Twentieth-Century China Pan Yuliang, Nie Ou and Yin Xiuzhen. Leiden University Press, 2016.

Wang, Cheng-Hua. “Rediscovering Song Painting for the Nation: Artistic Discursive Practices in Early Twentieth-Century China.” Artibus Asiae, vol. 71, no. 2, 2011, pp. 221–46.

Zhu, Pinyan. “The Republican Period.” Class Lecture. Atlanta, GA, ARTHIST_485.

Image Credits:

Renoir's Still Life with Flowers and Prickly Pears